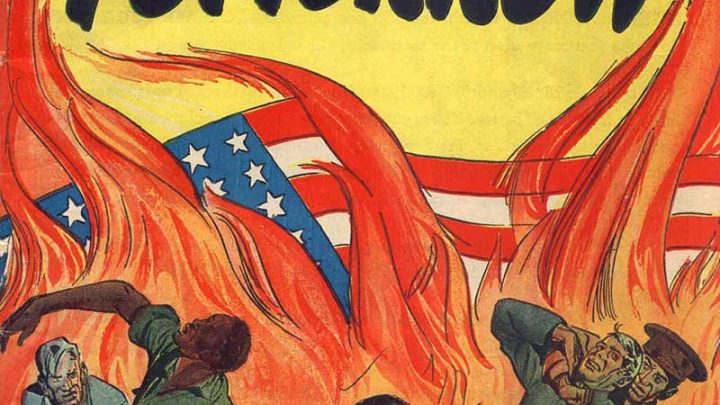

On July 23, 1967 Detroit became the latest U.S. city to erupt in riots that resulted in citizen deaths and massive property damage. Over five days, clashes between police and African-American residents led to one of the most destructive outbreaks of rioting, looting, arson, and sniping in U.S. history. 43 people died, and more than 2500 businesses were burned.

Detroit was the scene of only one of the 159 race riots that occurred across the nation during the long hot summer of 1967. From a distance of 50 years, it might be useful to reassess the community tensions and injustices that led to such intense and widespread violent clashes between black citizens and police. According to the Kerner Commission Report on U.S. Racial Inequality, the basic causes included:

- “Pervasive discrimination and segregation in employment, education, and housing, which have led to the continuing exclusion of great numbers of Negroes from the benefits of economic progress.”

- “Black in-migration and white exodus, which have produced the massive and growing concentrations” of impoverished African-Americans in major cities.

- Frustrated hopes and unfulfilled expectations following the earlier legal victories of the civil rights movement.

- “A climate that tends toward approval and encouragement of violence as a form of protest…created by white violence directed against non-violent protest.”

- The “frustrations of powerlessness” which are “reflected in alienation and hostility toward the institutions of law enforcement and government and the white society which controls them.”

- “The atmosphere of hostility and cynicism…reinforce by a widespread belief among Negroes in the existence of police brutality and in a ‘double-standard’ of justice and protection – one for Negroes and one for whites.”

In sum, the Kerner Commission declared that “the causes of recent racial disorders are embedded in a tangle of issues and circumstances – social, economic, political, and psychological – which arise out of the historical pattern of Negro-white relations in America.” It was this “explosive mixture” that led to a chain reaction of racial violence, and the commission report warned that “if we are heedless, none of us shall escape the consequences.”

The above video was produced at WILL Television in 1968 as part of the documentary series African American Life in Central Illinois. In 1967, Urbana, Illinois was not one of the 159 communities beset with riots and open racial violence. But its racial tensions are strongly evident in the documentary. In the above clip, local musicians LaMonte Parsons, Cecil Bridgewater, and Count Demon perform an original spoken word/jazz composition based on their experiences interacting with police in their own neighborhoods. The video was converted from 2 inch quadruplex videotape to 10-bit uncompressed digital video, and is now part of the collections of the American Archive of Public Broadcasting.

While American cities are not burning today, it’s worth considering if and how the conditions cited in the Kerner Commission report remain relevant. Protests and clashes following recent killings by police of unarmed African-Americans, many of them documented on video and shared on social media, have revealed a continuing divide among Americans in the interpretation of these events, and the contested meaning of race in today’s America.

In 1967 the Kerner Commission concluded that “our Nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal.” We offer here a suggestion, and invite a discussion: View this video from 1968, and let’s ask ourselves some hard questions about which direction we are now moving.